Getting to the bottom of it

A lot of our early stage material is improvised and then honed on stage – it gets better the more we perform it – but this ends up being a bit of a problem. We do the well-honed stuff, which just gets better and better, but whenever we try new gear it doesn’t immediately get the big laughs we’ve got used to, so we get frightened and scuttle back to the tried and tested routines. The incentive to try out new material diminishes because we’re addicted to the big laughs, and consequently the range of our material ends up being fairly small. In a year of shows at the Comic Strip Club, a tour of England, and a tour of Australia, we basically end up doing the Dangerous Brothers and a Sam Beckett piss take.

It’s frustrating because we know we’ve created some great comedy but don’t know exactly how we got there, or how to do it again, and we struggle to write ten long sketches for the Dangerous Brothers on Saturday Live in the mid-eighties.

Our method is to think of the single most exciting thing that can happen, then try to top it. As you can imagine this gets difficult once you’re half a page into a sketch. Once you’ve written ‘there is an enormous explosion’ at the top of the page it becomes difficult to think how to top it other than to write ‘there is an even bigger explosion’. And then you’re quickly onto ‘there is an even more biggerer explosion’ and you’ve kind of shot your bolt.

The sketches are seven minutes long – generally the same length as a Road Runner cartoon – but have twice as many stunts. And these are live action stunts: there’s a lot of punching, nipple tweaking, explosions, cannons, hammers, dynamite, being set on fire, smashing through windows, being shot in the head, a siege engine and even a live crocodile. I’m surprised they work as well as they do because the writing process is torturous, and when we finish we feel quite spent. We put absolutely everything we can think of into them and turn down the second series because we think there’s nothing left.

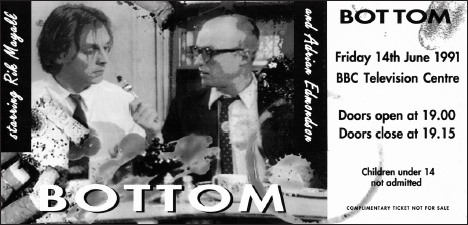

Saturday Live broadcasts in 1986. Bottom doesn’t appear until 1991 – a five-year gap. There’s never any conscious decision to stop the double act, but we both get very busy with other projects – quite a few of them together, like Bad News and Filthy Rich & Catflap – but the double act, or more specifically the writing part of the double act, goes into hibernation.

Alongside doing more Comic Strip Presents and the films with Les, I do a couple of projects written by Ben: Happy Families – in which Jennifer plays all four of my sisters and I play her imbecilic brother; together with Nige and Rik I do Filthy Rich & Catflap, also written by Ben; and Rik also works on Blackadder II which is a much funnier proposition to the first series now that Ben has joined Richard Curtis as co-writer.

Obviously we’ve already done The Young Ones too, so we’re basically learning a lot about the way Ben writes. Creativity is mostly subconscious theft – and not always your own subconscious. Once you become a writer it’s hard not to look at other writing from the other writer’s point of view. As a writer who’s also a performer you get to examine another writer’s work even more closely. And being in the rehearsal room with Ben as opposed to just watching, for example, another brilliant sitcom like Desmond’s, is a great learning experience.

Essentially he teaches us one of the fundamental truths of sitcom: you don’t have to start from square one every time. You don’t need to start with the big explosion. It is the characters that are funny. Take great care over creating your characters, and if they have conflicting desires, and the audience knows the characters well enough to anticipate those desires, hilarity should prevail. A lot of it is giving the audience what they’re expecting and making them feel clever about it at the same time.

By 1990 Rik gets a little bored with The New Statesman – a sitcom he’s been making since 1987 about a scurrilous MP, Alan B’Stard. It’s a great character but Rik knows he’s the only attraction in the show, and though that flatters his ego, I think he’s a bit lonely, creativity-wise. And I miss the old bastard too. We go for a drink, it feels like old times, and we decide to write something together.

When I think of Bottom I generally picture the little office where Rik and I used to write opposite the entrance to the Hole in the Wall pub in Richmond, and I think mostly of us laughing.

And laughing.

And laughing and laughing and laughing.

There was such a joy in it all. It felt untrammelled, unconstrained and vaguely unbelievable. There we were earning a sizeable wedge for just sitting on our arses trying to make each other laugh. It’s exactly what we’d been doing at university, but now we were getting paid.

Everything we did before Bottom felt like it was leading towards it, and, according to my Numskulls, or my interpretation of Sturgeon’s Law, it’s the best thing we ever do together.

Our initial idea is to call it My Bottom. We want the continuity announcer to say: ‘And next on BBC2 tonight – my bottom.’ We want people at work to be saying to each other: ‘Did you see my bottom on telly last night?’

The title is frowned upon by Alan Yentob, the controller of BBC2 at the time, and we reach a compromise by calling it simply Bottom. BBC2 is the home of new comedy throughout the eighties and nineties but there’s still a kind of intellectual snobbery against pure ‘childish’ humour.

As a small act of defiance in the face of this snootiness, instead of writing ‘THE END’ at the end of all our scripts we write ‘FIN’ as if they’re scripts from the Nouvelle Vague of French cinema and we are as intellectually highfalutin’ as Jean-Luc Godard or François Truffaut.

Being bottom becomes our theme anyway, so maybe Alan was right. It becomes about two sad losers at the bottom of the pile. It borrows heavily from Waiting for Godot – the two tramps waiting for some improvement in their unexplained lives. It borrows from Steptoe & Son – Harold the man yearning to climb out of the gutter, Albert doggedly holding him back. It borrows from Hancock’s Half Hour – Tony thinking himself a cut above, Sid recognizing they’re more likely a cut below. It borrows from Laurel & Hardy – two losers who only have each other. And it borrows from the Dangerous Brothers in its commitment to find ever more ingenious ways to beat the living daylights out of each other, but this time with a little more context.

We’ve finally sussed how to write without painting ourselves into a corner at the top of page one: we have two characters, based on hyper exaggerations of our own personas – one reaching for the stars but hopelessly inadequate, the other a bluntly philosophical berserker who’s prone to violence – and our writing days consist of ‘filling the larder’, as we call it, with material about how they would each react in certain situations: a library, famine, debt, love, police, death.

It is the characters that become honed. Imagine the Angel Gabriel – a character everyone knows, and whose behaviour is predictable – but take him out of the Nativity and think about how he would fare on a golf course, or doing his tax return, or trying to buy porn at a petrol station.

It’s a fairly unique process, making Bottom. The only sitcom before it written entirely by the main performers is Fawlty Towers. So we don’t have a map. I suppose we could ask John Cleese, but he’s a rather daunting individual.

In 1989, at the Amnesty fundraiser The Secret Policeman’s Biggest Ball, I do the Python sketch in which Michelangelo argues with the Pope about his painting of the Last Supper (Michelangelo has painted twenty-eight disciples, three Christs, some jellies and a kangaroo – the Pope wants a more conventional image). I’m playing Michelangelo, John’s playing the Pope. We convene at a cafe in Greenwich to read it through.

I’m frankly overwhelmed to meet one of my absolute heroes, but he is a very, very intense man. It’s like meeting the headmaster of comedy. I feel like I’m in Guybrow’s study. I begin to wish I was wearing two pairs of underpants. I have to put my script on the table, otherwise he’ll see how much it’s shaking in my hands. Obviously he’s done the sketch before, so he knows how to do it, but he delivers a long set of rules about the timing, and the playing of it, in an extraordinarily serious way. He takes his comedy very seriously. It’s like Latin – it’s full of rules.

I go away and learn the lines more thoroughly than I’ve ever learned my lines before, we get one more bash at it in the dress rehearsal, and then we’re on . . . and it goes down extremely well. We do it very well. Every joke lands. I don’t copy Eric Idle, I do my own Michelangelo, and it feels great. And John is brilliant as the Pope, but I’m not sure I’d want to work with him on a sitcom, because I can’t treat it as scientifically as he does.

He’s obviously a much more successful comedian than I am, and I’m not saying his method is wrong – it’s right for him – but I want to laugh all the time, I want it to be fun.

So we’re on our own. Again. We have to come up with our own methods, and the one we develop is this:

We meet at 10.00 a.m.

We make coffee and spend the first forty-five minutes talking about the world; about what’s happening with our families; about schools; about being annoyed at a supermarket checkout; about the news headlines; about different types of sandwiches; about what we’ve seen on the telly; about some behaviour we’ve seen on a bus; about where we’re going on holiday; about some gossip we’ve heard; about how to fix a dripping tap; about how to get hold of an actual gun; etc., etc. And somewhere within this jumble of ideas about the world in general something will eventually ping out. Usually after about forty-five minutes. Don’t lose your nerve.

‘Where would Richie and Eddie go on holiday? They’ve got no money, have they? Where’s the nearest holiday destination to Hammersmith? What’s the cheapest kind of holiday? What kind of holiday causes the most friction? What’s the worst kind of holiday?’

We then try and answer these questions, which invariably throws up more questions, and we start to fill the larder with ideas.

‘All right, suppose they’re camping. Whose idea is it? Why would they go camping? Is it an escape? Is it a bet? Who would be the best prepared? Have they got any equipment?’

Some of you might recognize that I’m describing the origins of the episode ‘Bottom’s Out’, in which Richie and Eddie go camping on Wimbledon Common. They basically camp in the dog toilet, they’ve remembered the can opener but forgotten the cans, there’s a tussle over a packet of chocolate Hobnobs and they land in the fetid pond, Richie falls in the fire, they hunt for Wombles with Eddie’s darts, using a tent pole to make a rudimentary blow pipe – Richie gets a dart in the head, a dart in the hand, and another in his arse – their tent is called a Stormbuster Mk IV (named after my own teenage tent) but is little more than a bivouac, Richie gets trapped in his sleeping bag, Eddie doesn’t have one, there’s a thunderstorm and the nudey flasher of Wimbledon Common gets his pubes caught in the zip of their tent and runs off with it . . .

I think my favourite bit is when Richie, trapped in his sleeping bag like an angry caterpillar, takes the peg mallet in his mouth and repeatedly hits Eddie with it. It’s deliciously insane.

It might sound easier than it is. In truth each episode takes about three weeks to write. Mostly because we have a burst of creativity after the initial ideas session and then go to the pub for lunch, after which we’re not much good for anything except what we call ‘secretarial work’ – arranging the ideas into some kind of order. So basically, a script is fifteen times two-and-a-bit hours.

But that little period, between around 10.45 and one o’clock, is the good bit. That’s when we offer up lines and laugh at each other. That’s the sparky bit. That’s when it feels like the lightning strikes. When we laugh like drains.

Some of the writing happens when you’re not thinking about it. You can be making the kids’ tea and you’ll suddenly think of how to solve a tricky link between lighting the gas stove and drying out the Hobnobs, or getting ready for bed and think about using a vest as a fishing net. Writing is a permanent state of mind, but the big bit, the fun bit, the bit that happens together, is that morning session.

Nearly everyone I meet who isn’t in the business imagines that the programmes must be improvised; that crazy stuff must just happen, that it must be wild, it must be mayhem, it must be chaos. I’ll admit some ideas are added to in rehearsal but the real mayhem and chaos takes place inside our heads during the writing period.

Once we get to the studio, and the pre-record of the trickier stunts, it’s about helping the SFX team and the technicians make that imaginary mayhem into reality. You can’t suddenly improvise when you’re pushing Rik’s head into a campfire. Ed Bye, The Young Ones’ floor manager who’s now our director, will have discussed the procedure for weeks: it’s a mixture of real fire that is extinguished quickly, smoke delivered through a tube, and an old Victorian magician’s trick called Pepper’s Ghost in which an angled pane of glass in front of the camera records a flame effect to the side at the same time as Rik leans into the fire. The two images combine.

Anarchy must be organized.

Ed is the best director we ever have and camera rehearsals are so intricate that they take a long time. There’s a lot of to-ing and fro-ing, getting the angles and the sizes right. I hate to burst the bubble of people imagining constant mayhem and chaos but I spend most of the camera rehearsals doing the crossword. It’s one of the calmest points of the whole process. I sit there on the bench on the set of Wimbledon Common, and happily work out my anagrams and cryptic definitions. It’s like a holiday – the calm before the storm of the recording in front of an audience.

Unfortunately the episode ‘Bottom’s Out’ doesn’t go out when planned. A fatal sexual assault takes place on Wimbledon Common just before the transmission date and it’s considered insensitive to show the nudey flasher shagging our tent.

When the next series goes out it’s tagged onto the end of the run but is pulled again when one of the suspects in the case goes on trial. It eventually goes out three years after its scheduled broadcast.

We don’t win prizes for Bottom but we do win an enormously loyal fan base who can quote our scripts at us in the same way that I can quote Laurel & Hardy. The first series gets the best viewing figures for a comedy on BBC2 until Absolutely Fabulous steals our crown a year later. Ed tells us with an amused grin that whenever ITV put on some crowd-pleasing special the BBC repeat an episode of Bottom against it to dent ITV’s viewing figures.

I think it’s one of the few times in our lives when we know exactly what we’re doing. But looking back at the dates I’m shocked by how much we get done in such a short time, it’s a real burst of energy: between 1991 and 1995 we create three TV series – eighteen episodes – and the first two live Bottom stage shows.

It’s made more extraordinary by the fact that we’re doing so many other things at the same time. I play Brad in The Rocky Horror Show in the West End; together we do Waiting for Godot (directed by Les Blair); I do another play, Grave Plots, in Nottingham; I shoot the series If You See God, Tell Him; The Comic Strip Presents makes The Pope Must Die and the special ‘Red Nose of Courage’ that goes out after the polls have closed on election night in 1992 – in which I play John Major as a clown who runs away from the circus, lured by the world of stationery. I write a novel, The Gobbler. All this while having three young children born in 1986, 1987 and 1990.

If Picasso had his blue period, this is definitely my purple patch. I can’t imagine how I could create that amount of material now. It’s taken me a year to write this book.